GENRE

GENRE

GENRE

GENRE

We invoke genre whenever we classify a film narrative. Video stores do it when they arrange their titles by categories such as "Action," "Comedy," "Drama." Like any generic classification, they help prepare viewers for what they will see, though the video store categories are often broad and imprecise. To better understand genre, we need to create categories that are not only in exclusive but also more definitive. When we do this, we find there is a moderately stable group of major genres—comedy, melodrama, action-thriller, crime, film noir, war, musical, Western, science fiction, horror—that flesh out and individualize the master narratives and tell us the stories we like, with the variations and invention that keep them interesting.

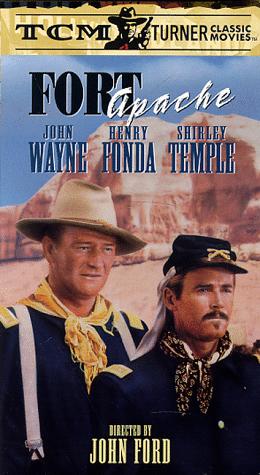

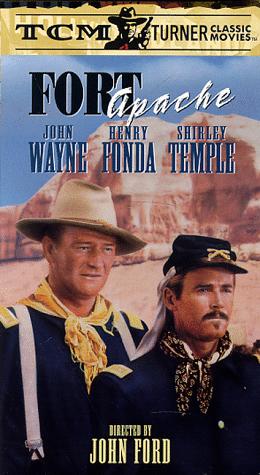

Subgenres: From within these large groupings, subgenres emerge. The action-thriller genre, for example, spawns such subgenres as spy films, and chase and caper films. Under and around crime film are its satellites, the gangster movie, the detective film, and film noir, which began as a subgenre and quickly emerged into a full-fledged genre of its own. Road movies like Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), Thelma and Louise (Ridley Scott, 1991), and Natural Born Killers emerge from the crime genre. Comedy and melodrama often cross. Forrest Gump is a melodrama with comedy; Sleepless in Seattle (Nora Ephron, 1993) is a comedy with melodrama. Genres are often inflected and changed by gender. The Western, a genre in steep decline since the early seventies, has seen recent attempts to revive it. One attempt, The Ballad of Little Jo (Maggie Greenwald, 1993), makes a strong case that a generic narrative can be retold by imagining what would happen were a women in the role usually reserved for a male.

Generic Limits: Genres can be quite supple, stretching and moving with the cultural demands of the moment. They help the viewer negotiate with the film, promising to provide certain narrative structures and character types that the viewer finds satisfying. But they have definite limits. For example, we saw in the last chapter that the action-adventure film can stretch to contain a great deal of self mockery and exaggerated, cartoon violence. But when the mockery becomes too severe, as it did in Hudson Hawk and Last Action Hero, audiences rebel. If a film is too self-conscious, the narrative bonds are in danger of being broken. If the audience feels it is not being taken seriously enough, it may not show up.

Genre and Gesture: Genres began to form as soon as films developed a narrative sense, as they moved quickly from merely showing things, such as a train leaving the station or two people kissing, to telling stories. When stories began being told, they quickly fell into recognizable types: romances, melodramas, chases, Westerns, comedies. As we said, much of this was familiar to audiences of the Victorian stage, vaudeville, and popular fiction. Types and stereotypes of villain and hero, bad woman and faithful wife, stories of captivity, heroic action, individuals wronged unjustly and then saved, chases and rescues both comic and serious were constructed, developed, and conventionalized into film from the stage within a matter of years. Acting styles, borrowed from the stage and further exaggerated into the pantomime of silent films, established the conventions of demeanor and gesture that, modified over time, arc still used and still specific to particular genres. A man or woman may no longer raise the back of a hand to the forehead to indicate melodramatic distress, but a man will bury his head in both hands and a woman will put both hands up to her mouth to show us she s shocked and frightened. Men still jut out their jaws to represent determination in an action film, and both sexes will look to the floor to show contrition, part their lips and roll their heads upward as a sign of passion in a romantic melodrama.

Robert Kolker, Film, From, and Culture