Horror

Horror

Horror

Horror

Horror as a Genre Unlike science fiction, with which it frequently overlaps, the horror film quickly established itself as a recognizable genre, beginning in 1896 with Georges Méliès's The Devil's Manor. The first of numerous versions of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was filmed by the Edison Company in 1910, and early filmmakers quickly and Arthur Conan Doyle. Important directors such as D.W. Griffith (One Exciting Night, 1922) and F.W. Murnau (Nosteratu, 1922) were drawn to the genre, as were serious actors like John Barrymore and Lon Chaney. Even the art film was comfortable with horror, as demonstrated in Robert Wiene's German expressionist classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). In this century, when horrors of many kinds are both common and constant, it is the horror tale that seems to have consistently captured and expressed our collective fears and anxieties. And horror has clearly found a home in the cinema; for, of all the mass media, it is film, experienced communally, that has liberated monsters and ghosts by making them at once visible and public.

The ability of special effects teams to create more and more convincing creatures, and the more refined skills of talented filmmakers to present them, add considerably to the inherent power of visual imagery to affect us. The essential difference between the classic and the more modern horror film is that of suggestion versus graphic presentation, or imagined as opposed to real horror. Expressionist horror films concentrated on mood, as did the RKO cycle produced by Val Lewton in the forties. In Lewton's Cat People (1942) both horror and suspense are generated in the justly famous scenes in which a woman walks alone at night in Central Park, accompanied by the ominous sound of rustling leaves, and when she swims alone in a darkly lit swimming pool, the play of shadow and light hinting at an evil presence as in the currently popular The Blair Witch Project (1999)..

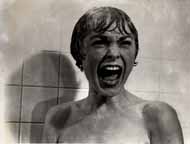

By the time of The Innocents (1961) (an adaptation of Henry James's The Turn of the Screw) and The Haunting (1963 and remade in 1999), however, restrained style and emphasis on character had begun to seem old-fashioned. Alfred Hitchcock had in fact changed the direction of the genre in 1960 with Psycho; the movie not only presented its most frightening moment, the shower murder, it also suggested that horror resides in everyday life rather than in the alternate worlds of the supernatural, the fantastic, or the Gothic. The subsequent rise of the "splatter film" was clearly inspired by Psycho, and it is no coincidence that Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) was based, like Hitchcock's film, on the case of real-life mass murderer Ed Gein. The recent so-called "slice and dice" films (Halloween, 1978 and Friday the 13th, 1980) and "living dead" movies (beginning with George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, 1968) are demonstrations of how contemporary special effects technology can depict increasingly gruesome and imaginative dismemberment and mutilation—usually at the expense of character, plot, and theme.

The other major difference in more recent examples of the genre is thematic: the tendency to locate the monstrous squarely "within" the normal rather than presenting it as a threatening "other." In this way, the contemporary horror film may be read as a critique of modern society, as many contemporary critics have argued, following the lead of Robin Wood's seminal 1979 essay, "An Introduction to the American Horror Film." Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980) exemplifies this reading of the horror film.A few early horror movies, perhaps most notably Tod Browning's Freaks (1932), offered social criticism of some kind; but those films generally ended with the horrifying element being conquered and the status quo being maintained. Some movies, like James Whale's classic version of Frankenstein (1931), at times present the creature as confused and misunderstood, but Jack Pierce's frightening makeup and Boris Karloff's stiff-legged strut ultimately make the creature more frightening than sympathetic.

By contrast, Night of the Living Dead suggests that the flesh-eating zombies are metaphorical projections of tensions within society and, more specifically, the family. It is no surprise that with the rise of environmental consciousness in the 1970s, movies such as Jaws (1975) have played on the sense of impending disaster resulting from pollution, as if nature itself were rising in retaliation. Whether the genre tends to locate the horrifying within ourselves (psychological horror), out there in the world (monster horror), or in the realm of the supernatural, it shows little evidence of abating in popularity.