Introduction

The acoustical design of the modern E-flat clarinet permits and promotes several unique sonic qualities (found in conventional sounds) from which many of today's new techniques have been derived. First, it allows an incredible range of colors, not only throughout its range, but on every pitch! These are apparent not only in single sounds, but in multiple sounds as well. It is ironic that the standard trend in E-flat clarinet performance practice has been towards timbric homogeneity (a goal that is impossible to attain!)! Secondly, the instrument is capable of a broad range of dynamics, from the virtually inaudible to FF. Finally, the instrument lends itself to extremes of technical activity (with regard to speed, register, and density of pitches) and, therefore, a broad range of different musical characters. Many composers, during the last twenty-five years, have "extended the techniques" of players simply by writing virtuosic music involving conventional sounds (i.e. many fast notes with rapid register leaps and extreme dynamic contrasts). The struggle of the performer attempting to realize this music has produced its own type of "new" musical interest and "new" techniques.

Contents

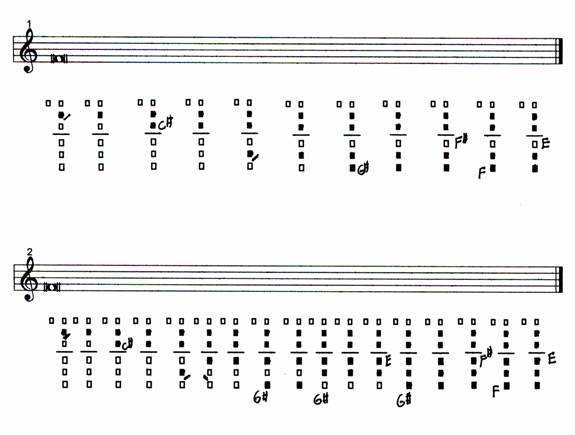

As a prelude to Chapter I, some general acoustic principles that the E-flat clarinet illustrates are presented, along with a brief theory of clarinet technique. The theory is based on a variety of teaching methods and concepts, including those of William Powell, Leon Russianoff, William Kincaid (John Krell), and George Townsend. This theory encompasses current ideas on connections between physical movement and legato technique, tempered by various acoustical considerations. It is believed that by connecting characteristics of methodologies of standard technique with the exploration of new techniques, one can successfully unlock further, reliable new techniques in a systematic fashion. Throughout The E-flat Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century an effort has been made to involve fingerings that are closest to standard patterns. One example of this relationship can be found in the ordering of practical microtonal segments; these are most successful when they involve chromatic fingerings of the right and left hands that lead from below to one of the twelve tones. In effect, the E-flat clarinetist need only learn a couple of variations of the standard chromatic fingering (Example #1).

Example #1

Chapter I is concerned with "Single Sounds." These are divided into three main categories: alternate fingerings (with an emphasis on the altissimo register), quarter-tones (including some easy conjunct segments), and microtones (equidistant scales). Four-hundred forty-six microtones (including quarter-tones) and one-hundred eighty-three alternate fingerings are discussed in The E-flat Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century in terms of acoustical origin, timbre, dynamic range, response, and stability.

Chapter II is entitled "Multiple Sounds." Four-hundred nineteen multiphonics and multiple sonorities are classified according to property (overtones or undertones), in practical sequences (according to identical left hand, or "short tube" fingerings), by pitch (bottom), timbre (texture), dynamic range, response, stability, and whether they are possible to begin with either their top or bottom pitches alone, with a gradual fade-in of their other voices. Seventy-one multiphonic trills are also briefly examined.

The third chapter is comprised of discourse, musical examples, and charts on other new E-flat clarinet resources that are not part of Chapters I and II. These include sounds of definite pitch and sounds of indefinite or ambiguous pitch (noise and pitch approximation). There is no end to the possible "other" E-flat clarinet sound resources, and this chapter merely touches the surface in a very subjective fashion.

The final chapter (IV) presents a discussion of the use of the high clarinets (C, D and E-flat) in orchestral music of the nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. The appendix contains a selected listing of published orchestral works that utilize these instruments. Very few composers have utilized the E-flat clarinet in solo or chamber music repertoire - some notable exceptions in chamber music are Hindemith (third movement of his Quartet), Webern (Op.16 trio with soprano and guitar), and Carter (Triple Duo).

Composers and E-flat clarinetists who plan to utilize some of the information presented in The E-flat Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century must be aware that all of the examples and charts were compiled from research undertaken with the standard Boehm-system E-flat clarinet (Buffet), and represented here at WRITTEN PITCH . Application of this information to other clarinet systems has not been attempted. Other complete studies would be required to determine what information is adaptable. However, since an overwhelming majority of American student and professional clarinetists play standard Boehm-System instruments, the practical value of this data can be substantial.

The material in this book is intended primarily to provide the imaginative performer and composer with points for departure. Even though the results of more than fifteen years of research have been tested for reliability by my students and many clarinetist colleagues, the refinement and musical utilization by composers in their music of the future is, ultimately, the most valued judgment.

The E-flat Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century is designed to serve as a companion to The Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century (1991 - E & K Publishers) - rather than repeat certain sections (for example, the history of multiphonics; acoustic principles of multiphonics), the reader is referred to the earlier study. It is important to note, however, that the E-flat clarinet is a very different instrument from the soprano clarinet (among its practitioners it is affectionately know as “the beast” or, in the words of conductor David Zinman, “the weapon”). It is difficult to play in tune (very few players use the same fingerings in the altissimo register because of differences in equipment and playing styles) and more resistant to play than the B-flat clarinet, but easier to articulate cleanly. The keys and tone holes are very close to each other and present challenges for those with average or larger size fingers. Because of the acoustical design of the instrument, both the altissimo register and color contrasts throughout its range are more limited than that of the soprano clarinet.

Most E-flat clarinetists are doublers, having first played (and continue to play) the soprano clarinet (B-flat). However, the fact that one may be a very good clarinet player does not necessarily mean that one is a very good E-flat clarinet player, even though I believe that one's approach to the smaller instrument should be no different from the standard soprano. The embouchure should be a miniature of one's regular clarinet embouchure, and “biting” should be discouraged. Careful and slow practice, as well as keeping the tongue position high, will help one to overcome the common “scooping” up to the correct pitch (the E-flat clarinet sounds a perfect fourth higher than the B-flat clarinet). Many players use B-flat clarinet reeds cut down to E-flat size, rather than E-flat reeds - they tend to help one create and control a tone that blends better within the clarinet family as a “small clarinet.”