| The Clarinet of the Twenty-First Century - E. Michael Richards |

CHAPTER 6 - Bass Clarinet

Single Sounds

It is an unfortunate myth which claims that extended techniques are only "effects" that are in no way related to traditional instrumental techniques.2 In fact, extended techniques are exactly what the term implies; extensions of conventional techniques. Throughout history, players and instruments have been forced to adjust to the times, or risk becoming obsolete. For example, composers, clarinetists/bass clarinetists and instrument makers have precipitated, often through collaboration, instrument design changes since the earliest clarinet was developed; the innovative composer, through his music, challenged the clarinetist, who consulted the instrument builder on ideas for mechanical improvements that would simplify the effort necessary to achieve the desired musical result. However, no design of the clarinet/bass clarinet has ever solved all of the awkward technical problems for the player. The most obvious proof of this statement is found in the fact that clarinetists/bass clarinetists have traditionally developed new or "alternate" fingerings to facilitate more reliable and musical results (suggested, and sometimes demanded by composers, conductors etc.) in performance. This has occurred despite the general emphasis by clarinetists/bass clarinetists in performance practice today on homogeneity of sound between adjacent pitches and registers. The usage of alternate fingerings in performance practice throughout the history of the clarinet/bass clarinet, but most especially since the early twentieth century when most clarinetists/bass clarinetists were playing instruments that had a greater number of easily manageable keys and thus more alternatives to choose from, demonstrates the existence of the concept of extended techniques, well before the middle of the twentieth century.3

Unfortunately, the clarinet/bass clarinet has evolved by exclusively empirical methods rather than by progressive theories. This, in addition to the musical requirements of past epochs, is another reason that has led both instrument-builders and clarinetists/bass clarinetists towards this single objective: what Bartolozzi has fittingly described as "the emission of single sounds of maximum timbric homogeneity throughout the range of the instrument."4 Rather than exploit the inherent qualities of the instrument, the clarinetist/bass clarinetist has been most often satisfied with refining the technique necessary for the performance of music from past musical epochs. Thus, during the twentieth century, much technique has become rigidly standardized.

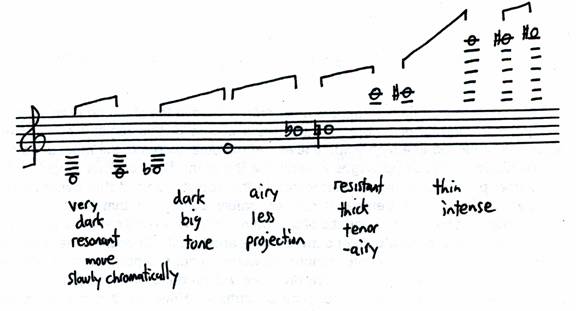

The desire of homogeneity of timbre in performance practice is especially baffling when one considers the unique characteristics of the bass clarinet, most obvious in comparisons with other woodwind instruments. It naturally possesses five registers of very different color, and of much greater contrast than any other wind instrument. The lowest three notes are very dark and resonant. The lowest register (chalumeau) tends to be dark with a big tone, and becomes diffuse as volume is increased. The throat register tends to be thin (airy; less projection) with potential for significant adjustments of timbre by the performer, while the clarion register is a resistant, thick, and airy tenor voice that becomes brighter as one approaches its highest pitches. The altissimo register is bright and becomes thinner and more intense as one ascends towards the highest pitch extremes of the instrument (Example #1).

Example #1 (click on register for mp3)

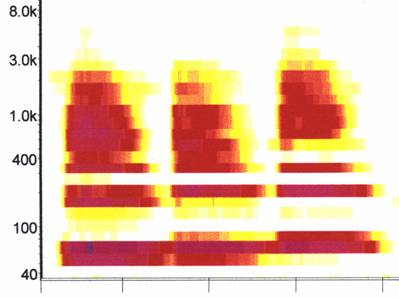

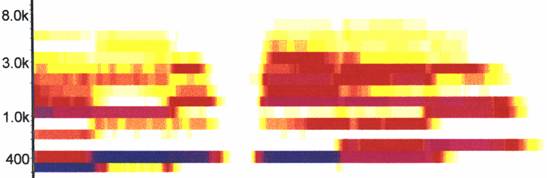

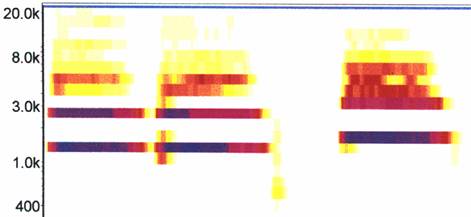

Spectrograms of these six registers reinforce the observations above. The lowest three pitches are rich in partials with a strong frequency band from 300-2000 hz. First, third, and fifth partials are clearly apparent, as are partials above the fifth.

C------------------ C#---------------- D

As the fundamentals move through the chalumeau register, higher partials become weaker.

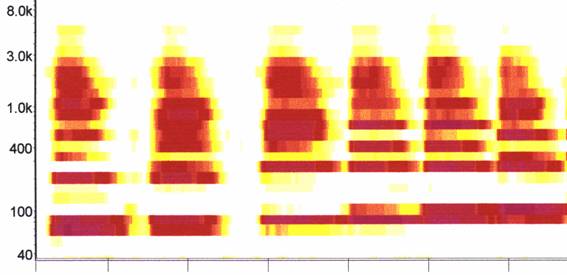

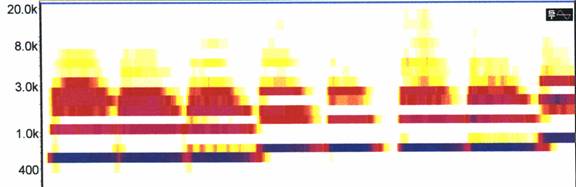

Eb------------------- E----------------- F-------------F#------------- G-------- G#

A---------- A#---------- B---------- C---------- C#---------- D----------- D#----------- E

Upper partials continue to weaken through the throat register.

E------------ F----------- F#--------- G--------- G#----------- A--------- A#

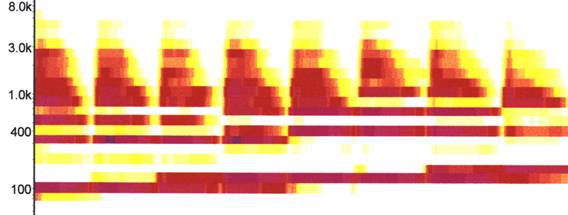

In the lower half of the clarion register, the fundamental and 3rd partials are particularly strong, but frequencies above 3000 hz. are weak. Frequency bands below 3000 hz. are more prevalent than in the throat register.

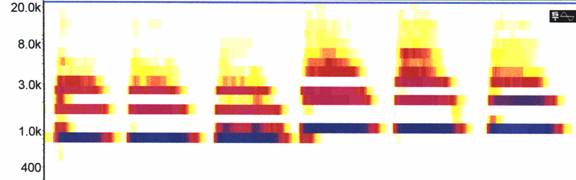

Clarion register:

B-------- C--------- C#--------- D--------- D#-------- E--------- F--------- F#

The first three partials are strong in the upper half of the clarion register, and partials above 3000 hz. gain strength at the top of this register.

G------------- G#------------------------ A------------------- A#

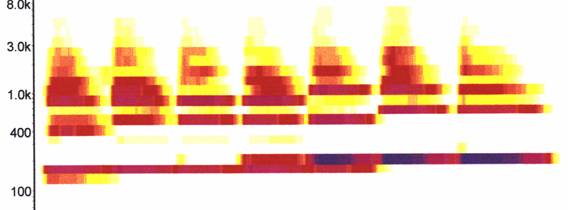

The lower part of the altissimo register contains strong 1-3 partials with gradually weakening frequency bands as the fundamentals ascend.

B--------- C--------- C#--------- D----------- D#--------- E---------- F---------- F#

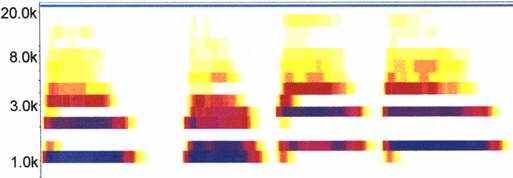

The strength of the first three partials continues through the middle and top of the altissimo register, and partials above 3000 hz. gain strength.

G----------- G#------------- A------------- A#------------- B--------------- C

C-------------------- C#----------------- D----------------- D#

E------------------ F---------------------------------- F#

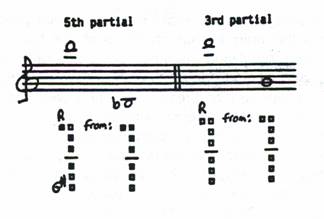

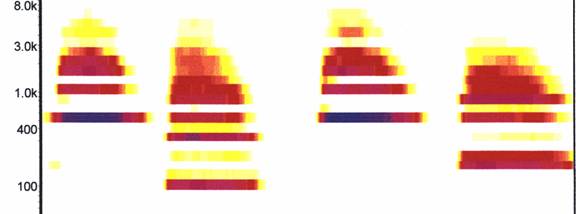

Because of the absence or weakness of clearly heard partials in this highest register, differences of dark and bright are not as applicable; thick and thin are perhaps more accurate descriptions, and usually relate to the particular partial level that is involved. For example, a pitch played on the third partial of a particular harmonic series may sound thinner than the same pitch played on the fifth partial of another particular harmonic series (Example #2).

Example #2 (click on music for mp3)

Viewing the spectrogram, one can see strong 1 st through 5 th partials in the first D. The second D fingering has stronger 4th , 5th , and higher partials, which contributes to creating a brighter/thinner sound.

D------------------- Bb--------------------------- D------------------------ G

Various reed styles or mouthpieces may push these qualities towards thicker or thinner extremes.

The effect of volume on timbre is most pronounced in the chalumeau register. In fact, the greatest contrast of timbre characteristics occurs in this register of fundamentals, when it is produced at a high volume level. At the other extreme, the most uniform timbre can be achieved in soft passages towards the top of the bass clarinet range, since there is a lesser presence of higher harmonics in this register and at this dynamic level. In between these outer extremes, it can be safely concluded that loud volume levels exaggerate the timbre characteristic of a certain pitch, while softer volume levels produce timbre matching at a middle point between dark and bright. Of course, the performer has a certain amount of control over timbre variables through embouchure or air pressure manipulation; increased embouchure pressure will produce stronger partials while less pressure results in the weaker presence of partials. However, this manipulation often distorts pitch level. The timbre characteristics that have been defined for individual pitches in this study are not the outcome of extensive or unusual embouchure manipulation.

In a more general sense, it is known that the harmonic spectrum produced by any instrument constantly changes in performance with every pitch and dynamic nuance that is played. In fact, there are even moment to moment changes in the balance of harmonics in every single humanly produced sustained tone.5 Other aspects of the sound that effect these changes include formants, phase, noise elements, presence of inharmonic partials, and transients (attacks). From all of the above information, it is clear that timbric homogeneity is an unlikely and unnatural eventuality for the bass clarinetist to achieve.

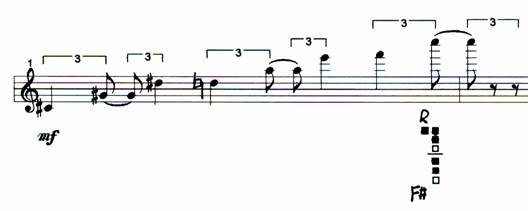

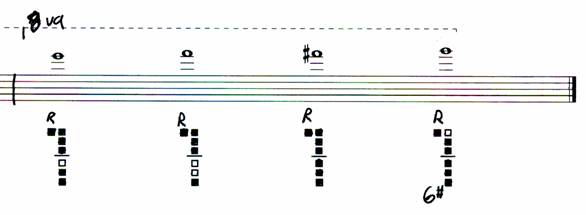

The altissimo register of the bass clarinet is the least explored register by composers, and provides a number of possibilities beyond the “as loud as possible” wailings most often associated with this tessitura. In magnificat 1 (variations) for alto flute, bass clarinet, and marimba, Linda Dusman effectively and imaginatively utilizes the top sounds of the bass clarinet. The phrase below illustrates a sequence of perfect fifths that culminates in a written C6 – the playing resistance experienced when using the fingering suggestion below allows this note to be controlled at a moderate volume.

Example #3 (click on music for mp3)

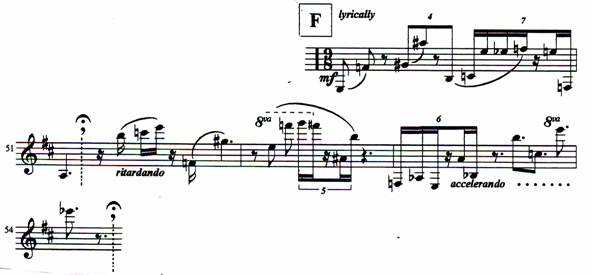

Later in the same work, Dusman writes lyrical phrases that span more than four octaves of the bass clarinet, and that weave among the other instruments in the trio. Fingering suggestions for E6-G6 follow the musical example below.

Example #4 (click on music for mp3)

for information on how to see/hear more musical examples, click here

|

||