"...the greatest possible perfection will be obtained only when theory and practice go hand in hand." 1

- Theobald Boehm

"It is already shown that four keys cause difficulties. How much worse it must be with six!" 2

- F. D. Castilon (1776)

Modifications of the design of the soprano clarinet since the major innovations of the first Klose/Buffet model (1839) were introduced have enveloped the work of many clarinetists and instrument builders from throughout the world. Some of the most significant of these, in terms of both theoretical and practical considerations, have been Romero, Schmidt, Stubbins, Mazzeo, and McIntyre, who have utilized principles of acoustics to create clarinets with more accurate intonation and greater timbric homogeneity. 3 However, strangely enough, the instrument that is used by more clarinetists in the world today (1991) is the standard Boehm instrument; an instrument that has changed very little in one-hundred fifty years and has generally not incorporated in a global fashion the alterations demonstrated by the aforementioned artist/builders. C. Mouzay, a twentieth century clarinetist, concurs:

....the plain Boehm system clarinet, still essentially as devised by Klose over 100 years ago, remains the basic established clarinet throughout Europe and most of America . Its principle faults include being unstable and out of tune throat tones, an unevenness of sound between registers and generally poor intonation. Manufacturers compromised and tried to develop a clarinet with the finest possible sound in one specific register -- the clarinet [clarion] register. 4

Why is this the case? Why has the evolution of the clarinet not always run parallel to man's knowledge of acoustics, which even supercedes the most advanced instrument designs?

There appear to be several answers, of differing validity, that are commonly given to these questions. Interestingly enough, these explanations also seem to apply to general attitudes of performance practice in the discovery, adaptation, and transformation of "extended techniques" into "standard techniques." These issues will be addressed in this chapter during and after an examination of the actual design changes of the clarinet since Klose, and a look at the basic acoustic foundations that the instrument operates from; for now, the issues can be outlined as follows: 5

1) the music industry (instrument manufacturers) and musicians are blinded by tradition - practice has always lagged behind theory

2) clarinetists do not wish to change their playing habits (to play on newly designed instruments), so the manufacturers do not have an audience of people large enough to support them financially if they introduce new, improved instruments

3) manufacturers can already make excellent instruments without relying on theoretical considerations

4) mathematical predictions, when compared to practical experiences (of performing musicians), do not always prove true - empirical methods are the only "safe" way to design a clarinet, since there are so many undetermined factors in wind instrument acoustics

5) since no individual player owns the same physical characteristics as another, no one instrument can be perfectly designed for more than one player

6) empirical methods are less expensive to employ in the manufacturing process than is the transferal of acoustical theories to practical designs

Changes in Clarinet Design: Who Demanded them First?

What has prompted instrument builders to change the clarinet if it has not solely been a craftsman's desire, in the scientific sense, for an ideal instrument? It becomes clear, when one examines the history of clarinet design, that most changes have been triggered by players. However, have players sought changes because of the demands of composers, or as a result of general problems that they have noticed with the clarinet? Martin Krivin, a composer and woodwind player from the New York area, suggests the latter through his belief that composers have generally merely followed in their compositions what performers have told them about the capabilities of their instruments.

The instruments were improved first. Composers have, for the most part, written their solos with a certain performer in mind and they usually conferred with them concerning the best way to execute their compositional ideas on the clarinet (or any other instrument, for that matter). 6

While this may be true, it is also likely that clarinetists have not requested design changes or improvements for idealistic reasons. Advancements are obviously related to practical problems encountered in performances of music written by composers! A variety of solutions to improve the tuning and homogenize the timbre of B-flat4 have been necessitated by the prominent use of this pitch in many works of music, for example. It is more accurate to see the evolution of clarinet design as a mutually precipitated one from clarinetists and composers.

A Brief History of 19th Century Clarinet Design, Before Klose

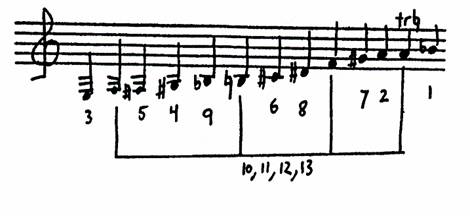

The clarinet that was widely in use at the turn of the 19th century was generally one of five or six keys. 7 These keys were the following, numbered according to chronological order of development:

Example #1

More elaborate systems were also apparently available and used by a handful of players. 8 Among these systems were some made in France, designed by J. F. Simiot of Lyons, who, as early as 1803, provided several additional keys. He was the first maker to move the hole of the register key to the upper side of the instrument, and thus avoid the problem of water condensation in the tone hole (it was eventually moved back to the underside and fitted with a tube to solve the initial problem). Simiot also fitted the left hand thumb tone-hole with a brass tube, for the same reason. 9 He is known to have exhibited a clarinet of 19-keys in 1828 with these modifications.

The most influential maker/clarinetist of the early nineteenth century, however, was Iwan Muller (1786-1854). Born in Russia , his early work took place in Germany and Austria where his invention of a 13-key clarinet "omnitonique" (ability to play in all keys) was first realized. These several changes in design, initiated around 1808, truly changed the significance of the clarinet. The instrument suddenly had the possibility to play in all keys with ease and security without changing the center joints ("pieces de rechange"); therefore, only one instrument (B-flat) was necessary for the orchestral musician. An improvement in general intonation would have been an indirect consequence as a result of the new found luxury of avoiding cold pieces de rechange in the middle of concerts. The thirteen keys, with the seven added keys numbered, are shown below:

Example #2

The most significant fact of Muller's clarinet, however, was not the increased number of keys; it was the change in design approach. Rather than placing tone holes simply where the fingers could reach them, Muller adjusted the situation and size of the tone holes according to laws of acoustics, and created key mechanisms to cover them. This application of a major acoustical principle of air column instruments provided a basis for the work of Theobald Boehm, about twenty-five years later.

An example of the realization of this principle can be found in Muller's new placement of the g2 hole, which had previously been placed higher than the g-sharp 2 hole in order to be reached! The hole for the little finger of the right hand had always been bored obliquely in a bulge of the tube with the base of the hole inclined slightly towards the bell. It was also a small hole, because it had to be closed by the tip of the little right-hand finger. Thus, the sound was stuffy, out of tune, and not at all matched with regard to color with other pitches around it. Muller solved this dilemma with a new key mechanism, so that the hole could be larger and closer to its acoustically correct position.

Muller also provided a solution to the legato fingering difficulties found between F2 and G-sharp 2, and E2 and F-sharp 2. Since alternate side fingerings did not yet exist, Muller built a mechanism for the right thumb to control. These soldered additional branches on the F-sharp/C-sharp and A-flat/E-flat keys were the first alternate fingerings for the long lever notes, which were later manifested in Klose's more elaborate system. This right-thumb mechanism was not popular with players of the time, but eventually led to rollers (invented by Cesar Janssen, a clarinetist in the Paris Opera, in 1823) that still exist today on the German clarinet.

Other improvements that can be attributed to Muller include rounded key cups (for better tone-hole coverage) instead of flat keys; German silver keys mounted on pillars instead of brass keys; stuffed leather pads (or animal intestines stuffed with wool) to replace simple leather pads; leather placed under keys, to minimize rattling; the body of the instrument made from darker and harder woods (cocuswood) instead of the lighter boxwood; a metal ligature, instead of a cord; and a more curved mouthpiece with a thinned, tapered reed that was more responsive and permitted a greater variety of articulations.

Muller migrated to Paris (c.1811) in an attempt to promote his 13-key clarinet. In 1812, a commission of musicians and players in Paris rejected Muller's clarinet because it could play in all keys as Muller claimed! "The Commission insisted that the tonalities achieved by the interchangeable pieces of the middle section of the instrument, which had until this time been used to change the pitch base, were in fact of great necessity to the subtlety of the art [they encouraged different colors]." 10 The physical inconvenience of awkwardly placed tone holes was ignored! Despite this defeat (Muller had to temporarily halt production of this instrument), time was on Muller's side. Even though practice did lag behind theory, the thirteen-keyed clarinet was widely adopted, at least in France , by the middle of the nineteenth century. 11 It remained in common use until the early twentieth century.

~next page~