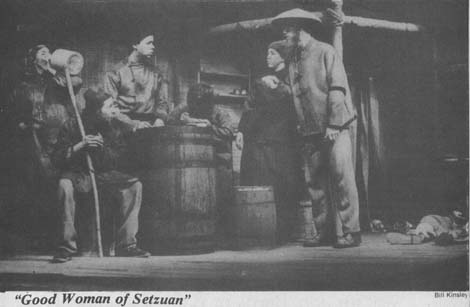

"Good Woman of Setzuan" cast: Peter Hertzgaard, Wendy Salkind, Dennis Marsico

Thus Brecht, the unorthodox Marxist, is making a leftist critizue of liberal philanthropy and welfare. Such piecemeal handouts only cause the poor to fight with each other for a chance at bare survival. And the other side of the seeming generosity practiced by Shen Te is the exploitive profiteering practiced by Shui Ta. In such a dog-eat-dog environment, religious notions of good must take a back seat to survival.

"I'd like to be good," Shen Te tells the gods, "But there's the rent to pay... I'd like to honor my father and mother, and speak nothing but the truth, and not covet my neighnor's house. I should love to stay with one man. But how? How is it done? Even breaking a few of your commandments, I can hardly manage.... Everything is so expensive; I don't feel sure I can do it!"

"That's not in our sphere," retorts one god. "We never meddle with economics."

In the UMBC Theatre, the deities stroll single-file across a wooden footbridge at the far rear and are silhouetted against a pale, blue-lit screen. Thus they seem distant and other-worldly. The stage, every bit as wide and dep as the seating, is filled with a marvelous set by Gavin Holmes. Three buildings are pock-marked stucco and tiled pagoda roofs surround a large, wood chip town square, where the villagers literally grovel in the dust.

Wendy Salkind's performance as Shen Te and Shui Ta holds the show together. As Shen Te, she meekly shuffles across the square and addresses the audience directly. She plaintively pleads for help in her conflict between goodness and survival. As Shui Ta, she struts about, gruffly offering her neighbors take-it-or-leave-it deals. Though Ms. Salkind is solid, she fails to capture the romantic impulsiveness behind Shen Te's generosity and her infatuation with Yang Sun, a handsome scoundrel.

Ms. Salkind is just one of six different UMBC Theatre faculty members contributing to this production. Gavin Holmes designed the set, and Terry Cobb designed the lighting. Alice Eve Cohen composed the clever if not memorable music for Brecht's many songs in the script. Cara Rowe was less successful with the costumes, a distracting mix of comic sci-fi outfits for the gods and slap-dash combinations for the townspeople.

Katherine Mendeloff directed. Though she has done a fine job with the three leads - Wong, Shen Te and Yang Sun - she has failed to do much with the rest of the 21-member cast. The crowd scenes are a jumble with any cohesive choreography. The hardest thing to do in a large-cast college production is to achieve consistent acting, but some of the acting int he minor roles here is wooden enough to start a lumber company.

The problem is overacting. The snooty women are self-caricatures with noses always turned upward, wrists always crooked daintily and voices always super-supercilious. The gods are never believably old and dignified; they always seem like young actors mimicking old people. The town's more despicable characters roll their eyes wildly and seem ready to foam at the mouth. Carolyn Spedden, Patty Fleagle and Jarvis E. Leigh do acquit themselves, however.

Only when the stage is otherwise cleared and the focus is on Ms. Salkindk J. Dennis Marsico as Yang Sun and Peter Hertsgaard as Wong do we actually believe we're in a poor Chinese village. Those moments come often enough to make this three-hour production worthwhile.

The play continues today through Sunday at the UMBC Theatre.

May 3, 1983

The cast of Brecht's "The Good Woman of Setzuan" frozen in a tense moment from the UMBC theater department's production. Directed by Ktherine Mendeloff, it is the tale of the god's search for the truly good woman. Finding their candidate in Setzuan, they are surprised to learn that she is the proverbial prostitute with the heart of gold. The play runs nightly at 8:00 p.m. through May 8 in the theate. For reservations call 455-2917.

Vol. 18, #27

May 2, 1983

The Very Good Woman

Leave it to Bertolt Brecht to make The Good Woman of Setzuan a prostitute. Leave it to UMBC to stage ambitious productions of Brecht.

This theatergoer fondly remembers a UMBC production of Caucasian Chalk Circle in 1977 and no doubt will remember their current The Good Woman of Setzuan as a handsomely mounted production. Indeed, their Brecht productions are so well thought out that this college production could more than hold its own with that of a professional regional theater.

Which is not to say all the news is good. Just as Brecht's Good Woman is about how hard it is to find goodness in an evil world, the goodness of this production is sometimes hard to see.

For one thing, --and this has more to do with Brecht than with the production -- the play's length might make even a sympathetic Marxist squirm in his seat. That old Marxist moralist Brecht drives home his point and then some in showing how a reformed prostitute, Shen Te, would like to run a tobacco shop and live honestly, but can only do so and stay in business by disguising herself as a mean businessman, Shui Ta.

A large cast of proletarian-types and capitalist-types fill out the sociological picture -- it's pre-Revolutionary China -- and the whole panorama is watched over by three gods looking for goodness in the world and a lowly water carrier who acts as a narrative liaison between gods and men.

Of course, Brecht's writing and Eric Bentley's translation are wonderful. For all his didactic fervor, Brecht

never totally loses his dramatic sense. Also, there are passages of proletarian poetry and song of great strength. However, the play is so long and repetitious that this reverent production might improve by being terser in the telling.

UMBC must have brought in truckloads of dirt for the village set, which by the end of the play is a dusty delight. When those poor peasants are rolling in dirt and squalor, they really are. Likewise, the peasant huts, costuming and other details of rural life have been closely observed and then effectively stylized.

Best of all, a bridge at the rear of the stage allows characters to pass over it in a near-silhouette. This not only pleases the eye, but reinforces Brecht's notion of character type.

Wendy Salkind, a UMBC Theater faculty member, is a powerful Shen Te, which only makes the surrounding large cast seem even weaker than they otherwise might.

Granted, Brechtian distancing techniques and broad characterizations often encourage stodgy delivery, but some of the supporting cast are wooden in ways that mark this as a collegiate show -- and yet I hesitate to say "amateur" in this regard, because many a professional production could learn a lesson from this one.

The Good Woman of Setzuan continues at UMBC (Baltimore, 455-2917) through May 8.

May 5, 1983

Solid performances by Peter Hertsgaard (left) and Wendy Salkind (center) make sense of The Good Woman of Setzuan.

Brecht Girl

By Crispin Sartwell

The Good Woamn of Setzuan

UMBC Theatre

The Good Woamn of Setzuan UMBC Theatre

College Theaters probably shouldn't try to stage Brecht, whose plays even when not particularly complicated or subtle, are long and difficult to perform. And perhaps none ought to stage The Good Woman of Setzuan, one of Brecht's most overwritten and purely didactic works.

But under the direction of Katherine Mendeloff, the UMBC Theatre recently made a well-considered attempt to bring this play to life. In many ways, such an attempt runs directly counter to the script itself, in which, as in much Brecht, the real drama is occurring at a (somewhat) deeper level among a cast of ideas. Mendeloff's direction, however, insists upon reading this drama in individual human terms, and it is this that holds the audience's interest and keeps us from being constantly aware, despite Brecht's huge contrivance and artificiality, that we are watching a play.

The program claims the The Good Woman of Setzuan is a parable about the impossiblity of goodness in an evil world, but, in the world of the play, evil seems equally impossible. More precisely, good and evil are incommensurable with the values that are necessarily generated in a society that starves.

Three gods (or, if you prefer, Illustrious Ones) pass through the town of Setzuan, looking, like starry-eyed Marine recruiters, for a few good men. Only Shen Te, a prostitute played with warmth and intellitence by Wendy Salkind, offers them shelter. The gods decide that she's the only really good person they've met, and when they hear she's selling her body, they give her some money. With this, Shen Te starts a tobacco shop, but soom finds that

her neighbors want to share in her good fortune. She is about to lose everything by being too charitable, when it occurs to her to dress as a man (creating her business-mogul cousin, Shui Ta), toss the paupers off her doorstep, and make the business profitable. It's Tootsie in reverse (though it's far less amusing) -- woman is too nice, dresses for success as a man, proceeds to kick butt.

As Shui Ta does all sorts of naughty capitalist things like employ (read, exploit) the local peasantry, Shen Te continues to get it in the neck because of her virtue. Trusting a dashing pilot, she's impregnated and dumped. She can't bring herself to marry a wealthy, but vivdly hog-like shopkeeper.

Finally, as Shen Te becomes more and more submerged in Shui Ta, the peasants want to

know what's become of their good woman, and Shui Ta is accused of her murder. At

a trial before the three gods, the evil man says "I have a terrible confession to make,

I am she(the good woman)," thus driving home the point (ethical ambiguity) with a sledge

hammer.

Gavin Holmes' set is simple and gives the vivid impression of a dirt-poor village,

and Alice Eve Cohen's music adds oddly appropriate atmospheres on homemade instruments.